Electric cars are more efficient, cleaner, and certainly a lot quieter. Yet, for every positive thing about them, there is a big pile of disinformation floating around the internet aimed at torpedoing their inevitable rise. You can believe some of it, but an awful lot of it is fake, wrapped in particular politics and perpetuated by those with vested interests in the status quo. Or sometimes its fed just by someone retweeting a meme they liiked. Here are just some of the truths and lies about electric cars.

THE UGLY TRUTHS

EVs are not as much fun to drive

Well, the hypercars are fun, but only in a straight line. In a straight line, electric hypercars are downright thrilling.

Get in a Rimac Nevera, a Pininfarina Battista, or a Lucid Air Sapphire, floor the accelerator, and your entire brain will be compressed to the size of a walnut as your vision blurs and all your guts are pressed against the back of the seat while a little voice from somewhere inside your head that you didn’t even know you had starts saying in a squeaky meter, “heeeellllpppp meeeeee!”

Apart from the hypercars in a straight line, the rest of the time electric cars are far less engaging to drive. Go around a corner and you’re just going around a corner.

In a gas car with a manual transmission and a hearty exhaust burble, you’re anticipating the entry, easing on the brakes, operating the clutch, matching the revs, downshifting, divebombing the apex, and smoothly and confidently powering out.

So, until they figure that out, like making kale and hummus taste good, you’re going to have to fake it.

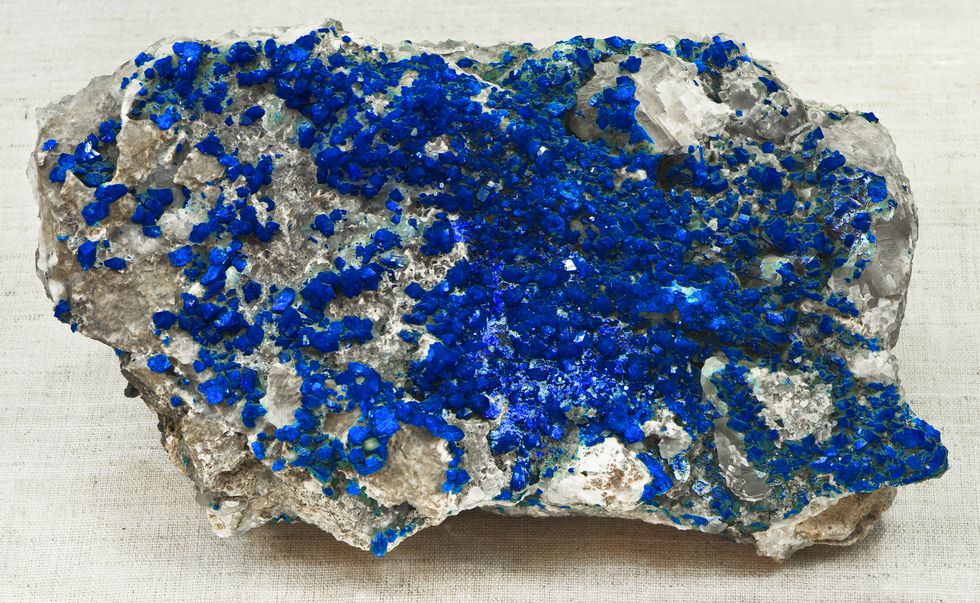

Cobalt is sourced unethically, sometimes

Cobalt is an element used on the cathode of a battery, the positive terminal. If you don’t include cobalt in the cathode it could overheat or even catch fire.

Mining cobalt is often done with lower-than-OSHA standards however, mostly in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where they’re not as strict about who does the work.

CHILD LABOR

The non-partisan government think tank The Wilson Center says Congo has more than half the world’s cobalt and is where 70 percent of cobalt mining takes place. Of 255,000 miners in the DRC, 40,000 are children, the Wilson Center said.

Companies like BMW, Volkswagen, and Samsung are part of a group called Cobalt for Development formed “to support ethical and safer practices in the DRC’s cobalt mining industry.” Tesla joined a group called the Fair Cobalt Alliance, which has many of the same goals. Other EV makers are still working toward ethical minerals. So the problem is being addressed.

And while child labor is something all nations must fight to eliminate, the sad reality is it is used to produce everything from bamboo and bricks to cabbages, carpets, cashews, cattle, and chocolate all over the world, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

Child labor is also used to mine coal in at least five countries, including China. So the problem—and it is a big problem—is not confined to just cobalt mining.

EVs take longer to charge, at least they do now

While great strides are being made in fast-charging—take Nyobolt’s six-minute charge we wrote about last month—across the board it still takes some planning to go on a long drive in an electric car.

For regular EV use, you can just plug in at home when you get there and unplug the next morning when you head off to work. Rates can be lower overnight, so it makes economical sense.

But the public electric fast-charging network as it stands now is kind of a mess (with the exception of the Tesla Supercharger network, which everyone seems to love, but which not everyone can access yet). Most public chargers are owned by different companies that all want you to download their app, sign up for life, and never use anyone else’s plugs for as long as you own your car.

OUT OF ORDER

Good luck calling those 800 numbers, too. Anecdotal experience suggests roughly half the public chargers in any given metropolitan area aren’t working for one reason or another.

A recent JD Power survey on EV charging concurs: “…charging station availability is a top barrier to the greater adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) as perceived by US consumers today,” the study said.

But there weren’t a lot of public gas stations at the dawn of the internal combustion vehicle, either. Things are getting better all the time.

Range Anxiety

Like most anxieties, range is based on fear.

Write down how many miles you actually drive each day. The average in the U.S. is 37 miles, according to the U.S. Dept. of Transportation. You could recoup that every night with the same plain-old 120-volt wall plug that’s powering the very computer on which you’re reading this.

But that doesn’t stop the anxiety. That problem is real. “Yeah, but what about when I want to drive to Vegas, man???” There are chargers available for that. Some even work. The public charging network is flawed at the moment, but getting better.

Affordability

We sit here and write about how great the Rolls-Royce Spectre is, but it costs over $250,000. That Remac Nevera mentioned up above is $2.4 million. So yes, many EVs are expensive.

Nonetheless, the Chevy Bolt EV starts at $26,500, and the Nissan Leaf for $28,040. And some electric cars qualify for a $7500 Federal tax credit. So maybe this one belongs in the Lies section, below…

THE DIRTY LIES

All you’re doing is changing where the pollution is coming from

One of the favorite talking points of EV slanderers is that, while there are no tailpipe emissions coming from EVs, the pollution is coming from coal-fired powerplants just a few miles away that produce the electricity needed to operate them, thus making EV drivers flaming hypocrites!

COAL, NOT SO MUCH

First of all, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, less than 20 percent of power plants in the U.S. run on coal; 40 percent run on natural gas, another 20 percent on nuclear, and the rest on renewables, the latter accounting for 21.5 percent of the grid and growing.

So, unless you’re recharging in West Virginia, your power source is almost certainly cleaner than coal. It’s also cleaner than coal in most countries in the world, according to a study by Cambridge, Exeter, and Nijmegan universities in Europe published in the journal Nature in 2020.

“Under current conditions, driving an electric car is better for the climate than conventional petrol cars in 95% of the world,” the study said. That includes the United States.

The grid can’t handle it

The grid is evolving now, just as it has always been. There was no electrically driven air conditioning in the first half of the 20th century, for instance. Gradually, consumers installed a/c in homes and offices across the country and no one suffered blackouts because of it.

The same could happen with the adoption of electric cars (which is taking place over the course of decades, by the way, not all in one week).

POWER TWO-WAY STREET

In fact, the presence of large EV fleets could help balance the grid when EV batteries are used as a storage medium for electric energy during the day, when solar power is available, and then discharge that stored energy in the late afternoon and evening when demand continues.

Recharging that takes place during the day when solar is available could mitigate or eliminate the need for costly new power plants to meet peak loads, according to a 2023 study by MIT researchers.

Electric cars can also recharge at night, when owners drive home and plug them in. Overnight charging could easily use up excess grid capacity when no one’s using electricity.

The battery will need to be replaced often and at great expense

All batteries in U.S.-market EVs come with a federally mandated warranty of eight years and 100,000 miles. California requires a warranty of 10 years and 150,000 miles. Rivian offers an eight-year or 175,000-mile (whichever occurs first) warranty for its large pack battery with Quad-Motor drivetrains.

Granted, after that, nobody knows. There isn’t enough data yet to make a precise chart about battery life, so maybe this one belongs up in the Ugly Truths portion of the story, or somewhere in between.

LONG-LIFE BATTERIES

A crowd-sourced study by Tesla owners worldwide, cited in our sister publication Car and Driver, said Tesla batteries typically held at least 90 percent of their original charge after 150,000 miles of driving. Predictive modeling by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory indicates that today’s batteries may last 12 to 15 years in moderate climates or 8 to 12 years in extreme climates.

Recurrent Auto, which provides car dealers and private party buyers with vehicle reports for used electric cars, says that in its community of 15,000 EV drivers, the rate of battery failure is only 1.5%. So you probably won’t need a new battery for a long time.

Still, if you do, there is scant info on how much a new battery will cost, and that cost will surely change within the next eight to 10 years as battery manufacturing technology progresses. JD Power said the replacement cost for a Tesla Model 3 battery is $13,000, though data available now suggests you won’t need to replace it.

Electric cars don’t work in cold/hot climates

That was certainly true of the first electric cars, before thermal management of battery packs got better.

EV batteries work best at 70 degrees F. If your car is plugged in and charging, part of that energy is going toward maintaining that optimum temperature for battery performance.

A 2019 study from AAA found that “on average, an ambient temperature of 20 degrees F resulted in a 12 percent decrease of combined driving range and an 8 percent decrease of combined equivalent fuel economy.” But when you turned on the interior heater, it resulted in a 41 percent decrease of combined driving range and a 39 percent decrease of combined equivalent fuel economy.

The U.S. Dept. of Energy found the same 41 percent figure. Consumer Reports did its own study with five different EVs on a sub-freezing day and found a 25-percent reduction in range across the board.

As more efficient heat pumps replace resistance heaters in EVs, efficiencies should improve. A heat pump compresses air to heat it and sends it into the cabin, using from a quarter to a third less energy than your typical space heater, which eats electricity like a toaster. But you will still get a drop in efficiency in cold weather. So plan ahead.

All those batteries are going to contaminate landfills

Again, there’s not enough data at this stage of EV adoption to know exactly what’s going to happen with used batteries. So far, most of them are still in cars.

There are promising developments in all areas, however. For instance, consider battery repurposing before battery recycling.

MULTI-USE BATTERIES

A company called B2U in Lancaster, California, takes partially depleted EV car batteries and repurposes them to capture electricity from solar farms during the day, then sends the stored electricity out onto the grid when the sun goes down. And when they’re done being repurposed, they can be recycled.

VW opened its first battery recycling plant in Salzgitter, Germany, two years ago, with the ability to recycle 95 percent of an electric car’s battery pack.

Redwood Materials, near the Tesla gigafactory in Carson City, Nevada, says it is “creating a closed-loop, domestic supply chain for lithium-ion batteries across collection, refurbishment, recycling, refining, and remanufacturing of sustainable battery materials.”

Redwood says “to make batteries sustainable and affordable we need to close the loop at the end of life. We’re localizing a global battery supply chain and producing anode and cathode components in the U.S. for the first time—from as many recycled batteries as possible.”

Battery recycling startups are popping up everywhere, too. We met the team at Li-Cycle at the ACT Expo in May. Li-Cycle says it will specialize in recycling Li-ion batteries by shredding them, dropping the shreds in an aqueous solution that allows the heavy metals to sink to the bottom, and then recovering the various minerals: lithium carbonate, nickel sulphate, cobalt sulphate, manganese carbonate, and copper sulfide, all needed to make, or remake, a battery. Li-Cycle says it can recover up to 95 percent of battery-grade materials in its recycling process.

Other battery recycling firms popping up. Again, this is still a little bit of the wild west. As more EVs hit retirement age, more companies will pop up to take up the charge, so to speak.

Conclusion

So, are electric cars the way of the future? It certainly seems inevitable. The technology continues to advance, both in drivetrains, batteries and infrastructure. Just because some of the details are not as established as internal combustion infrastructure, doesn’t mean they won’t be soon. The biggest problems may not be technological as much as social, scraping away all the misinformation being pumped out there by interests heavily invested in the status quo. Overcoming that may be the toughest obstacle of all.

Have your own myths to dispel or truths to reveal about EVs and the infrastructure supporting them? Please share in the comments below.

Mark Vaughn grew up in a Ford family and spent many hours holding a trouble light over a straight-six miraculously fed by a single-barrel carburetor while his father cursed Ford, all its products and everyone who ever worked there. This was his introduction to objective automotive criticism. He started writing for City News Service in Los Angeles, then moved to Europe and became editor of a car magazine called, creatively, Auto. He decided Auto should cover Formula 1, sports prototypes and touring cars—no one stopped him! From there he interviewed with Autoweek at the 1989 Frankfurt motor show and has been with us ever since.

Read the full article here