New technologies have a tendency to blindside. When color TVs were introduced in the 1950s, for example, they seemed like a flop. The devices were expensive, programming was scarce, and after a decade on the market few homes had one. Then suddenly prices dropped, a ratings war ensued, and in just a few years most U.S. households were watching “The Jetsons” in its futuristic palette.

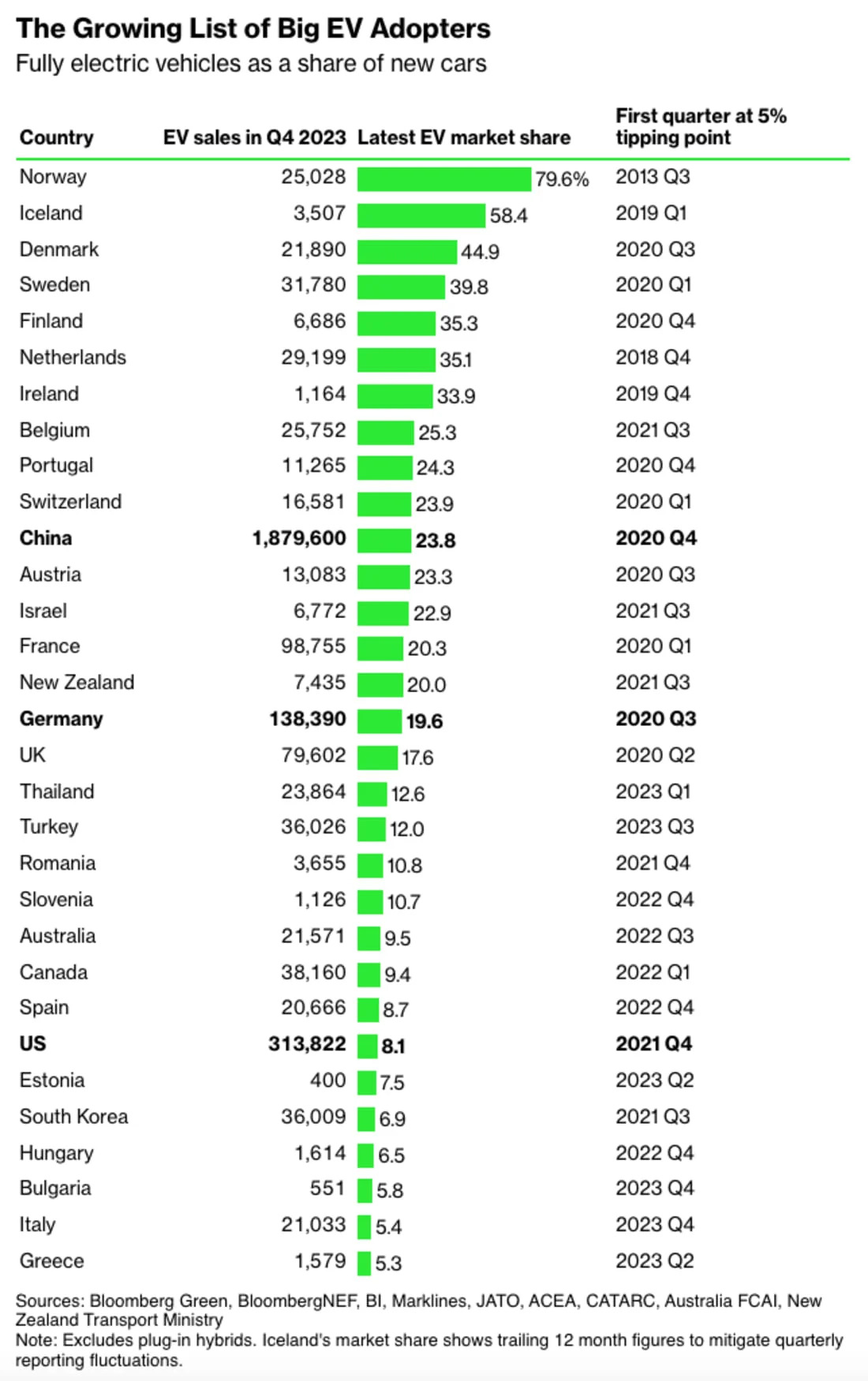

A comparable shift is currently underway with electric vehicles, according to a Bloomberg Green analysis of adoption rates around the world. By the end of last year, 31 countries had surpassed what’s become a pivotal EV tipping point: when 5% of new car sales are purely electric. This threshold signals the start of mass adoption, after which technological preferences rapidly flip.

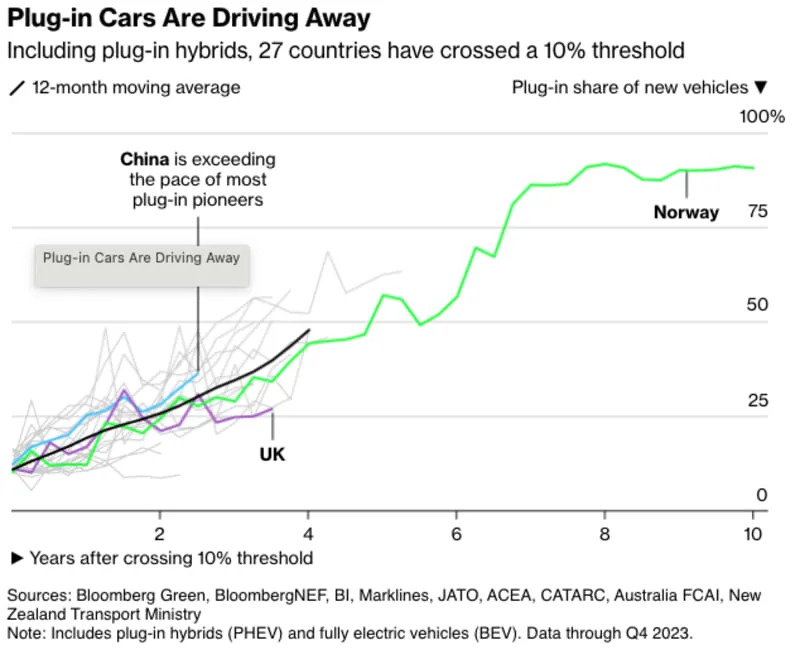

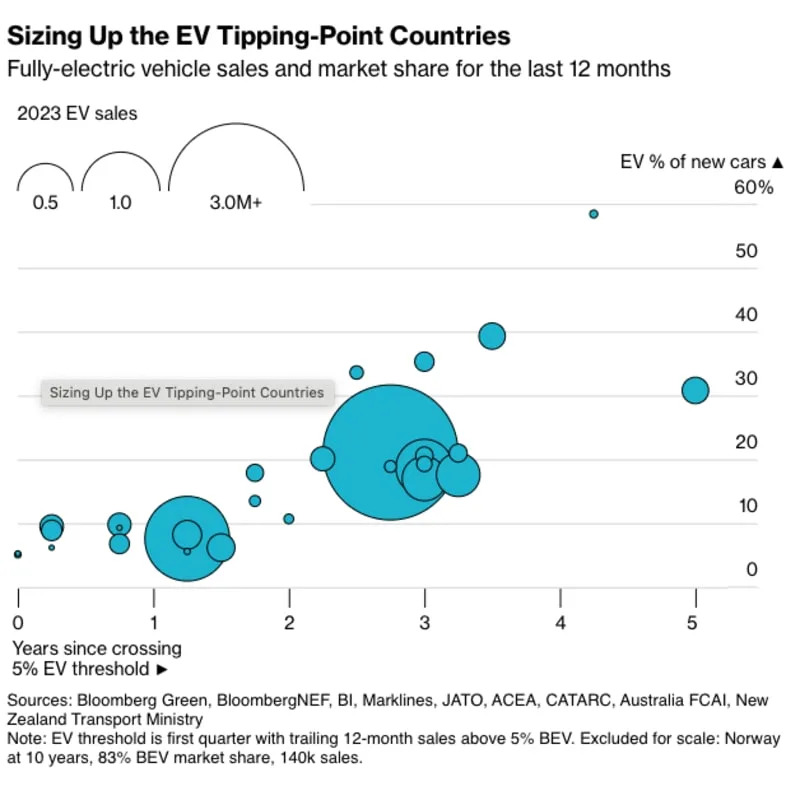

When we first completed this analysis in 2022, only 19 countries had passed the 5% tipping point. Last year, that number soared as EVs spread across four continents. For the first time, some of the fastest-growing markets were found in Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia. The trajectory laid out by countries that came before them shows how EVs can surge from 5% to 25% of new cars in under four years.

Why is 5% important?

New technologies — from televisions to smartwatches — follow an S-shaped adoption curve. Sales move at a crawl during the early-adopter phase, before hooking into a wave of mainstream acceptance. The transition often hinges on overcoming initial barriers such as cost, a lack of infrastructure and consumer skepticism. The tipping point signals the flattening of these barriers. While each country’s journey to 5% plays out differently, timelines converge in the years that follow.

“Once enough sales occur, you kind of have a virtuous cycle,” said Corey Cantor, an EV analyst at BloombergNEF. “More EVs popping up means more people seeing them as mainstream, automakers more willing to invest in the market, and the charging infrastructure expanding on a good trajectory.”

Several countries crossed the tipping point last year in blazing fashion. Thailand emerged as Southeast Asia’s EV pioneer, surpassing the 5% threshold in the first quarter of 2023 and then rising to nearly 13% of new car sales by the last quarter. The transition was supercharged by the opening of Thailand’s first domestic EV factory, owned by China’s Great Wall Motor Co.

A similar story played out in Turkey, a country that was barely on the radar for EV adoption a year ago. The Turkish auto company known as Togg flipped the switch with the release of its first battery-powered car — the T10X — an SUV that competes squarely with Tesla’s Model Y. Sales of the electric Togg set a blistering pace. Turkey crossed the 5% tipping point in the third quarter, and by the fourth quarter it was the fourth biggest EV market in Europe.

While this market-share approach to EV tipping points shows how fast the transition to electric cars can take hold, it doesn’t preclude year-to-year slowdowns or setbacks due to supply-chain disruptions, economic downturns, bankruptcies and politics. Analysts at BloombergNEF expect fully electric and plug-in hybrid vehicle sales to increase about 22% this year globally, decelerating from the last several years, though not dramatically changing the long-term outlook for EV adoption.

The U.S. underperforms

The U.S. tipping point didn’t arrive until the end of 2021 — relatively late for a country with its economic clout. American drivers demanded EVs with longer ranges than the earliest models offered, and the U.S. preference for pickup trucks and large SUVs required bigger batteries than the nascent supply chain could handle.

Two years after crossing the tipping point, the U.S. continues to lag the countries that came before it. Fully electric cars accounted for 8.1% of U.S. auto sales last quarter, far short of the 18.1% average for 20 countries at the same point on the adoption curve. The only country with a smaller share of EVs at the two-year mark was South Korea, a nation whose range anxiety rivals the U.S..

Not a single country thus far has taken more than three years to go from 5% to 15% EVs — which means the U.S. and South Korea will either break from the trend in 2024 or will require a sudden acceleration in sales to catch up.

While the analysis above is for vehicles that run on batteries only, some countries, primarily in Europe, were quicker to adopt plug-in hybrids. The U.S. mostly skipped over hybrids, which have smaller batteries backed by a gasoline-powered engine, but automakers are now turning to them to forestall a costly showdown with ever-cheaper electric cars out of China.

Since hybrids don’t require the same level of infrastructure or consumer commitment as fully electric cars, the earliest phase of adoption can be more erratic. A consistent tipping point for this broader category of EVs isn’t reached until 10% of new vehicles are hybrid or fully electric, according to Bloomberg Green’s analysis. The U.S. was just shy of the mark, with 9.9% market share for the second half of 2023.

A tipping point for the world

The countries that have now passed the EV tipping point account for two-thirds of the world’s auto sales. That still leaves large swaths of the global population behind the curve. Nevertheless, a tipping point may be approaching for India, Indonesia and Poland, significant auto markets where EVs have been on the rise. In South America, a major push underway by China’s BYD could provide the spark for widespread adoption beginning with Brazil.

Applying this framework to the entire planet, the 5% EV tipping point was crossed in 2021. In the fourth quarter of 2023, fully electric cars accounted for roughly 12% of new cars soldworldwide. The same forces that drove so many car buyers to try their first electric model — falling battery prices, more chargers, better performance — continue to make EVs competitive in new markets.

Methodology notes:

Tracking begins when the tipping point threshold is exceeded for a single quarter. However, a fleeting period over 5% may be subsequently excluded if it proves to be anomalous. Iceland’s quarterly market share figures show a 12-month trailing average to mitigate wide swings in quarterly reporting.

Read the full article here