Haven’t you heard? We built our own Honda Motocompacto scooter. It’s dimensionally identical to the real thing and uses many legit Honda parts, but it’s a lot faster than stock. Or at least, it will be by the time this story ends. It’s a Motocompacto Type R.

If you haven’t read the first story, I recommend doing so before this one. This piece mostly covers the driving experience and related subjects. The other story details the building of the Motocompacto Type R; how we made the chassis; how we got a Motocompacto motor; how it all came together.

Providing The Juice

The first big item was getting a battery mounted in the scooter’s body. It’s a little narrow in there, but there’s otherwise plenty of space. The stock Motocompacto battery is a 36-volt (nominal) unit of around 250 watt-hours. That’s a nice capacity for a scooter, but I didn’t want to use it, not only because there’s likely a performance-limiting management system wired into it, but also because the assembly is around $300 from Honda, which is really expensive for a pack of that capacity. Instead I started with a battery I knew well: one ripped out of a Hoverboard.

If you’ve ever looked for a cheap battery on eBay, you’ve probably seen these.

These 36V packs can put out around 40 amps of current for a while before they get unhappy. They only contain 155Wh of energy, but the price is right at just $40. Full of 18650 cells, they’re a common choice for scooters, e-bikes, and other light electric vehicles. Their only real downside is they have pretty bad voltage sag under load, which effectively gives the scooter a little less power than if it were using a larger battery. All you need to know for now is that there are many fun ways to solve that problem which we’ll explore later.

I installed the hoverboard pack and wired up the throttle. Then, I routed the mechanical brake. Eventually, I want to get rid of this brake by utilizing very strong regen, but for now I figured I might as well put it in. When all of that was done I added the headlight. I used a sodium-ion 18650 cell to power it. I bought a bunch of sodium-ion batteries a while ago out of curiosity and decided to use one for this purpose. This is not the last time you’ll see them.

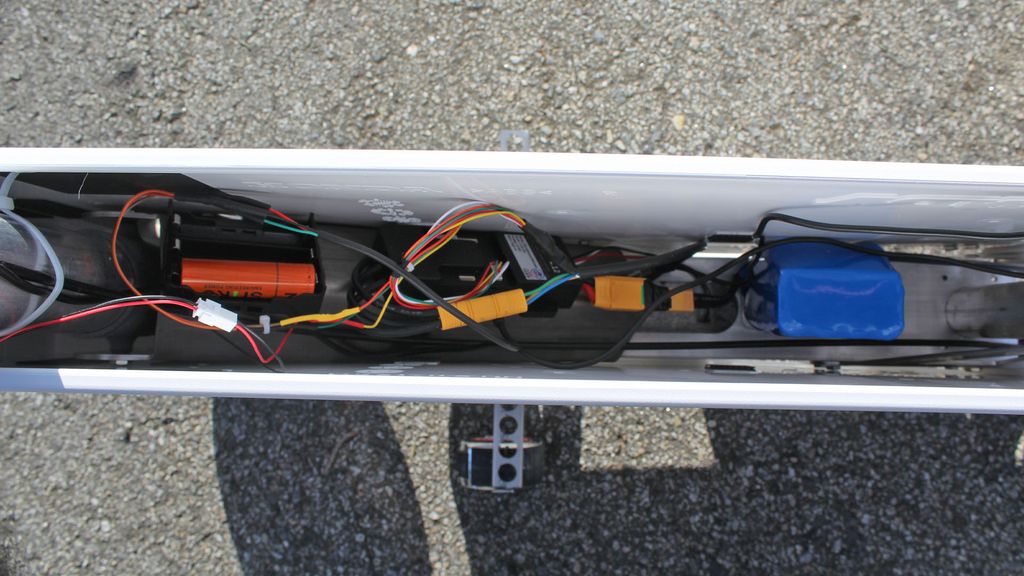

There’s really not much wiring going on inside this thing, but it still manages to look like a mess.

Finishing Touches

I weighed the scooter before riding it. At 37.2 pounds, it’s about 4 pounds lighter than the factory version. With that in mind, I set the current to 14 amps which would give me a stock amount of Motocompacto power. Having never built something this light before, I didn’t know what to expect in terms of acceleration.

And it was very slow. I haven’t driven a stock Motocompacto, but let’s just say I’m pleased that I’m able to alter this one’s output. At 490W, this thing could barely handle the gentle grade of my driveway. I guess that shouldn’t be surprising for ⅔ horsepower, but I was expecting more.

Turning up the power is as simple as adjusting a value in the VESC tool software. This can also be done wirelessly via Bluetooth.

So I turned it up to one horsepower, which was a little better. At this amount of current, the stock scooter would blow its internal fuse. 745W was still not enough, though. I wanted this thing to take off and accelerate hard.

I went back into the garage and did a quick health check on the scooter, which meant I looked around to make sure nothing was smoking. Bad for people as well as electronics. Nothing was even warm, so I turned it up to 40 amps. That’s about the max these batteries are willing to provide and would give me 1,440W, which is about two horsepower.

This is a picture of the scooter with a slightly different battery which you’ll read more about later, but it gives you an idea of what’s going on under the skin.

When electric motors receive too much current they generally get hot and make a sort of TV static squealing noise, at least in my experience. If you’ve ever driven a turbocharged car that breaks up under boost, it kind of feels like that. You want it to go faster but it just isn’t having it.

Anyway, this one did that. At full throttle it really complained, the phase wires to the motor were getting warm, and the whole thing was generally not having a great time. In my experience, around 35A is really the end of the world for these kinds of small hub motors. So I turned it down to 35A and mellowed out the throttle curve. That made it just right.

I was really enjoying it, and on the way back to the garage it stopped accelerating very suddenly. As it turns out, the little clips used to keep the motor shaft from spinning had been sheared wide open by the newfound torque. The sudden jolt unplugged the motor from the rest of the scooter. I bent everything back into place and now it’s fine. I’ve since redesigned the clips. You can see how much weaker the old ones were. As a rookie scooter designer, I’ll take that one on the chin. As a side note, future runs will include a helmet.

The increased torque has also revealed that the tolerances on my front end are a little loose. When you go wide open, you can physically feel the fork trying to pull itself off the scooter. Maybe that part shouldn’t be plastic. Speed wobbles are a problem too, but I’m not sure if that’s specific to my design or more a result of the minuscule 29.2” wheelbase and very small amount of caster angle. Improvements are on the way in that department as well.

Changes

The whole reason I did this project is customizability, and you’ll be seeing more on that front. We’ll be able to change out the batteries, alter the “tune” on the drivetrain, and modify the hardware to get a better end product. Since we did this whole deal from the ground up, anything is possible.

I kinda wish I could’ve just bought a stock Motocompacto to do all of this, though. I understand the Honda isn’t supposed to be a dangerous toy with a hair-trigger throttle, but that should ultimately be up to the owner to decide. A lot of enthusiasts find electric vehicles unappealing because manufacturers lock them out of the tinkering and tuning process. That’s silly when altering the performance of an EV is as simple as a few keystrokes on a laptop. Maybe I’m drifting out of my lane here, but if you want people to like your toys, they have to be able to play with them. The Motocompacto in particular doesn’t even run at a deadly level of voltage.

Critiques aside, this thing is still fun to ride and surprisingly practical. Even without folding, it fits handily in the back of my car. The large square body also provides a lot of space inside for storage, or a rat’s nest of wiring in my case.

I think there are many potential modifications here, and as soon as the next piece of the puzzle arrives, the Motocompacto Type R will return. I want to do a top-speed run, but I need to mentally prepare myself for that and tighten up the steering. If you want to see anything else in particular, leave a comment and we’ll consider trying it. More riding footage is on the way, too. The weather has not been kind lately.

Image Credit: Mike Juergens, Peter Holderith

Read the full article here