According to some accounts, NASCAR has used 15 different point systems since 1949 to determine its Cup Series champion. Other research places that figure between 14 and 17, including some changes that were barely different from the ones before.

Whatever the number, there have been these extremes:

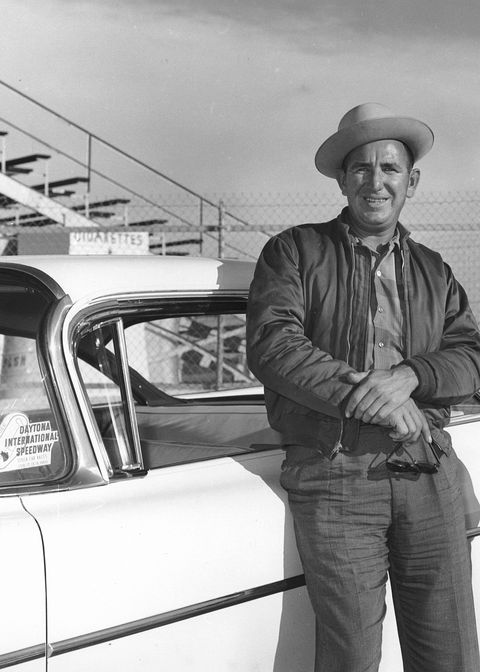

Richard Petty won one of his seven championships by 6,028 points (1967) and another by 5,032. Rex White (1960) and Ned Jarrett (1965) won their championships by more than 3,000 points. Both of Joe Weatherly’s titles (1962, 1963) came by more than 2,000 points.

On the other hand, Kurt Busch’s 2004 championship came by 8 points. Alan Kulwicki’s 1992 title came by 10, another of Petty’s came by 11, and Rusty Wallace’s 1989 championship margin was 12 points.

In the closest finish in NASCAR history, Tony Stewart and Carl Edwards ended the 2011 season dead-even at 2,043 points. Stewart won the Cup based on his 5-1 “most victories” tiebreak with his fifth victory coming over second-finishing Edwards in the Homestead finale.

In some cases, Petty, White, Jarrett, and Weatherly clinched their championships with races in-hand. Petty, in fact, would still have been the 1964 and 1967 champion even if he’d skipped the last few races of those seasons. Contrast that to Stewart vs. Edwards, and to Kulwicki, who needed to lead one lap more than Bill Elliott to ensure the 1992 Cup in the Atlanta finale. (FYI: That was Petty’s last Cup start and Jeff Gordon’s first).

Granted, those 13-17 different systems have skewed the competitive image of NASCAR since points were once awarded in far greater numbers than today. In truth, it seems the sanctioning body changed its championship criteria almost yearly.

Consider:

There were times when finish-position points were paid according to race distances.

At other times, track lengths were factored in. Race purses were frequently part of the championship equations.

Lap-leader and victory bonus points were awarded some years and not others.

In some cases, only a portion of the grid earned points; those finishing poorly got nothing.

There were years when Daytona qualifying paid points and times when half-points were used.

No wonder fans couldn’t figure it out.

Latford and Co. Saves the Day

But in 1974 three NASCAR employees rode to the rescue—temporarily, at least. Joe Whitlock, Bob Latford, and Phil Holmer gathered at the Boot Hill Saloon in Daytona Beach after NASCAR president Bill France Jr. called for yet another system. He wanted something consistent and fair, something fans might understand. Using cocktail napkins, the men scratched out a system that awarded points in descending order throughout the entire field. To encourage hard racing, they offered lap-leader bonus points.

The “Boot Hill System” stayed largely unchanged until Matt Kenseth muddled everything by winning the 2003 title with only one early-season victory. After winning at Las Vegas, he strung together 23 top-10s to win the Cup by 90 points over three-race winner Jimmie Johnson. (Eight-race winner Ryan Newman finished sixth, plagued by inconsistency).

As much as anything, Kenseth’s maddingly-consistent (boring?) season kick-started NASCAR toward today’s Playoffs. Introduced in 2004 as “The Chase,” only the top-10 in points were eligible for the championship during the last 10 races. Those races would still feature 40-car fields, but only 10 drivers were racing for the aptly-named “Big Hardware.” (Busch won it by eight points over Johnson).

Ten was chosen because nobody outside the top-10 after the regular season had ever rallied to win the Cup. The addition of two “wild card” drivers in 2007 was the Chase’s first change. Its second came in 2014, when four more drivers were added, allowing officials to create the four-round, 16-driver, 10-race, tournament-style Playoffs we have today. NASCAR executive Brian France introduced the radical “elimination format” early in 2014.

At the time, he spoke of “Game 7 moments” to determine the championship. His perfect world would have four championship hopefuls charging through the last turn on the last lap of the season’s last race. In effect, he wanted a racing version of a World Series walk-off homer; a last-second Super Bowl field goal; a buzzer-beating 3-pointer in the NCAA finals; a 72nd-hole eagle to win The Masters.

“The whole idea is you can’t relax,” France said during a NASCAR-related radio broadcast that week. “Every lap matters. Stages matter. Many years ago, you could cruise around and build up a big point lead. You can’t cruise around at all. You’ve got to be on it. I think that’s what people really enjoy.

“I’ve always believed that (racing hard) brings out the biggest moments, too. It brings out the driver talent. Almost every year at Homestead (now, Phoenix), the top three or four in finishing order are usually the top playoff contenders. What does that tell you? Like any athlete, when they have to do exceptional things, they rise to the moment. And that’s fun to watch.”

While many older fans like nothing about the recent Playoff formats, the current 10-race, 16-driver, four-round elimination format seems to be working. Despite MLB’s looming playoffs, the specter of football at all levels, and the opening of NBA and NHL camps, interest in NASCAR’s championship run remains high. That’s especially true with the added pressure of “name drivers” being eliminated after races at Bristol, Charlotte, or Martinsville.

In the last nine years—since the Playoffs were expanded to 16 drivers—the average championship margin has been 3.6 points. Of course, the Championship 4 was designed to produce such numbers, but the championship will still come down to the last race at Phoenix on Nov. 5. The last eight champions have won the season-finales at Homestead and Phoenix, approaching France’s longed-for “Game 7 moment.”

Where They Stand Heading to Bristol

Officially, 16 drivers remain championship-eligible going into Saturday night’s 500-lapper at Bristol. Only recent Darlington winner Kyle Larson and Kansas winner Tyler Reddick are assured of moving through to Round 2 at Fort Worth, Talladega, and Charlotte. Four Bristol drivers are below the Round 1 cutoff line: former champion Martin Truex Jr. is a concerning -7 below, Bubba Wallace is a worrisome -19, Ricky Stenhouse is a more-worrisome -22, and Michael McDowell is a daunting -40.

The four lowest-ranked drivers after Saturday night will be dropped from the Playoffs. Similarly, the four lowest after the Fort Worth, Talladega, and Charlotte round will be eliminated. And the four lowest in points after Las Vegas, Homestead, and Martinsville will be eliminated. That would leave only the Championship 4 still standing when the season ends at Phoenix.

The highest finisher among them—regardless of where that is overall—will be the champion. Phoenix may or may not produce a “Game 7 moment,” but no matter what happens it’ll absolutely, positively beat winning the title by 6,028 points.

Contributing Editor

Unemployed after three years as an Army officer and Vietnam vet, Al Pearce shamelessly lied his way onto a small newspaper’s sports staff in Virginia in 1969. He inherited motorsports, a strange and unfamiliar beat which quickly became an obsession.

In 53 years – 48 ongoing with Autoweek – there have been thousands of NASCAR, NHRA, IMSA, and APBA assignments on weekend tracks and major venues like Daytona Beach, Indianapolis, LeMans, and Watkins Glen. The job – and accompanying benefits – has taken him to all 50 states and more than a dozen countries.

He’s been fortunate enough to attract interest from several publishers, thus his 13 motorsports-related books. He can change a tire on his Hyundai, but that’s about it.

Read the full article here